Greetings! If you’re on this page, you likely either clicked the link by mistake or are my blood relative. But in case you are here intentionally, then let me begin by welcoming you to the wide and weird world of electric utility rates. In this series, we’ll explore the electricity sector using a bill as our guide. Why do such a masochistic thing to yourself? Well, according to very smart people, electrification (replacing fossil-fueled appliances & processes with their electric alternatives) is critical to averting the worst impacts of climate change. But the way rates are structured today, electrification is way more expensive than it should be, which discourages adoption of things like electric cars and heat pumps. Boo! So here, I’ll try to impart what I’ve learned after nearly a decade spent studying and designing electricity rates and utility customer programs (like this, this, this, and this).

I empathize deeply if your first thought is, “How could we comprehensively cover the lifeblood of modern civilization by reading a sales receipt?” Allow me to counter: when is the last time you looked - I mean really looked - at your utility bill? You would remember a dizzying array of charges, rates, and gobbledygook masquerading as technical jargon.

The utility bill is a much less magical version of Pandora’s Box that holds the key to vital questions like “why is electricity in [insert state here] so expensive?”, “why is it cheaper (in some places) to heat a home with natural gas than electricity?” and “how much will I save by buying an electric car?” Our bills also reflect decades of design choices (some good, some bad but well-intentioned, some bad and malicious) by electric utilities, elected representatives, regulatory authorities, and trade groups. But once you understand the bill, you will understand not only what’s wrong with electricty rates but also what changes are needed to spur a rapid transition to clean energy across all sectors of the economy. This series is for anyone curious about how to advocate for those changes. And if you’re just looking to learn more about electricity rates in general, that’s fine too!

Last bit before the fun begins: this series will always be free, but if you would like to support as a paid subscriber, all proceeds go towards an awesome organization called Run on Climate working to enact bold climate policy at the local level. Paid subscribers will have access to bonus content, Q&A, and a concierge service where we’ll step through your bill to identify ways to save money and cut carbon.

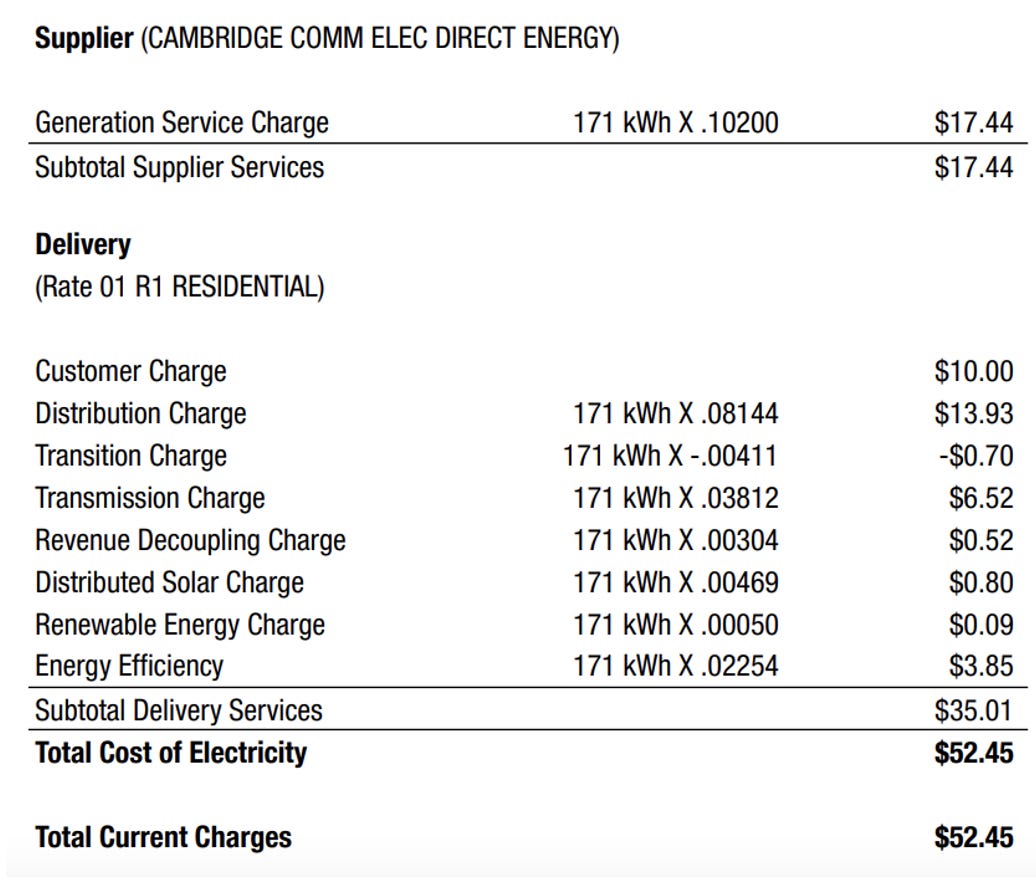

Without further adieu, here’s my most recent bill:

Figure 1: My bill

You must be thinking, “How on earth are there NINE separate line item charges for a single product?” We’ll cover them at a high level here then dive into details in subsequent posts.

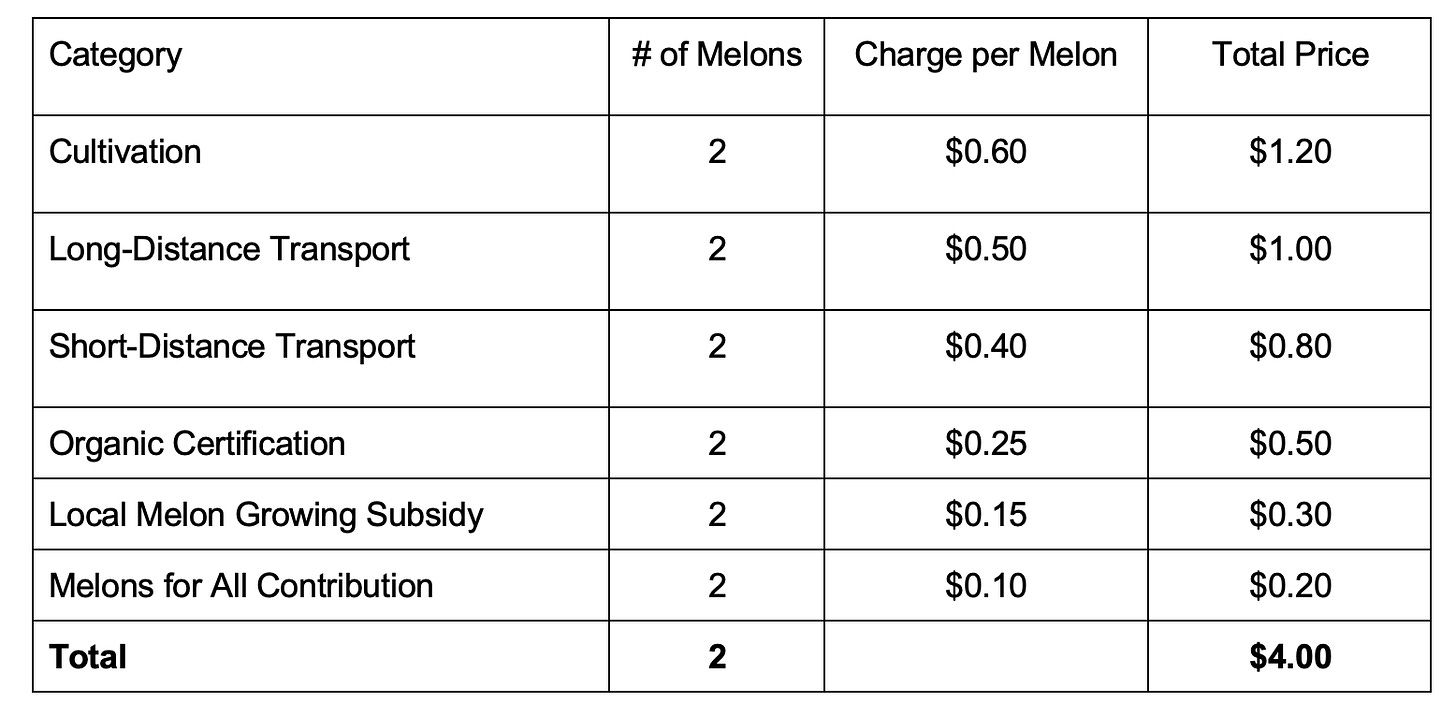

For a point of reference, consider a grocery bill. Each line represents the cost of one or more of the same item. Calculating the total cost is simple: multiply the price per item by the total number of items purchased.

Figure 2: A simple grocery receipt with only the most essential items shown

Electricity is different. There aren’t apple-flavored electrons and strawberry-flavored electrons. While the uses for electricity are incredibly diverse (clean your clothes, power your vehicle, cut grass, illuminate a room, heat a space, try and fail to mine a bitcoin, etc), each unit of electricity is identical; electricity is what is known in economics land as a commodity good. And so the NINE lines on the bill don’t reflect a difference in product; they reflect a breakdown of the costs of producing and delivering that product. It would be equivalent to seeing the following on a grocery bill under the price for melons:

Figure 3: A hypothetical grocery receipt if utilities ran supermarkets

Now you’re probably thinking, “Why don’t utilities just combine all the charges into one?” They could easily do that and 99.9% of customers would not care one iota. But let me offer two guesses for why they don’t:

Unlike melon prices, the cost of electricity is highly regulated, meaning that every penny of every charge is scrutinized by government agencies to ensure that utilities are not overcharging

Utilities knew that one day I would write a blog series about electricity rates and wanted to provide me ample fodder for discussion

I hope I’ve convinced you that melons and electricity are different. Now it’s time to examine each of those NINE charges using melons as our link to human speak.

On my bill, “kWh” (or kilowatt-hours) is the equivalent of “# of Melons” and each line is a different type of cost category. Bear with me here but I’m going to try to map each electricity charge to a melon charge, with a few exceptions.

Generation Service Charge = Cultivation

Otherwise known as the “supply charge,” this reflects the cost to generate electricity. Depending on your utility, that electricity may come from any number of sources (wind, solar, hydropower, nuclear, coal, natural gas, oil, biomass, etc). But once it is generated, the electricity is indistinguishable. In some states, the supplier is the same company as the distribution and transmission utility (vertically integrated). In others, customers are free to choose their supplier (deregulated).

Customer Charge

A flat monthly charge that reflects the utility’s overhead costs, including office space, salaries, and the horrifyingly ugly plastic cylinders…I mean meters…bolted to the sides of houses that measure consumption. In melon world, think of this like an annual membership you pay to be allowed to shop at the supermarket (like a Sam’s Club or Costco model). Except that for electricity, you must pay the charge because you can’t shop at other supermarkets- fun!

Distribution Charge = Short Distance Transport

The cost of maintaining, repairing, and upgrading the “distribution grid.” The distribution grid is what delivers electricity to end-use customers (i.e. homes, businesses, schools, factories).

Transmission Charge = Long Distance Transport

Not to be confused with the transition charge, this funds the cost of the transmission grid, which transports electricity over long distances. The transmission and distribution grids are linked by substations, otherwise known as the fenced-in, scary looking, and audibly buzzing facilities you were told not to climb into as a kid due to risk of being barbecued. Figure 4 illustrates the different grid components.

Figure 4: Illustration of electricity’s path from generation to consumption. Credit: VP.Start

Transition Charge

Specific to Massachusetts, this charge in theory covers the cost of transitioning to a smarter, more resilient grid. I really tried to come up with a clever melon analogy for this one but gave up. Luckily, my dad is more creative and proposed hydroponic, genetically engineered melons that not only taste great but boost immunity. This charge would be as if the government allowed melon producers and distributors to collect a surcharge on all sales to support development of said enhanced melons.

Revenue Decoupling Charge

This one also broke the bounds of sensible melon analogies. Here’s my best shot: imagine that the aforementioned hydroponic melons were the only defense against corona viruses. The government, with the ultimate goal of ensuring access to pandemic protection, sets out to protect the financial solvency of the melon industry. To smooth year-over-year volatility, regulators order supermarkets to set the price of melons at cost and allow melon companies to earn a regulated profit on their investments in cultivation and delivery.

In the electricity sector, “revenue decoupling” is a regulatory model whereby utilities’ profits and revenues are separated. Under previous compensation models, the utility had an incentive to sell as much electricity as possible. That translated into minimal effort into encouraging customers to use less electricity, for example by purchasing energy efficient appliances. With revenue decoupling, the utility earns a profit on its capital investments; all other expenses (including the cost of generating electricity) are passed through to customers. We’ll come back to this concept in later posts, but for now, it’s sufficient to understand this charge as an adjustment that syncs up expected revenue with actual revenue. That way, the utility doesn’t build up a debt or surplus that needs to be corrected in the future.

Distributed Solar Charge = Local Melon Growing Subsidy

This charge translates directly into subsidies for people to install rooftop solar. The reason for this subsidy is that if the utility paid rooftop solar owners purely the value of their generated electricity, it would (in many cases) not be enough to cover the investment. So per state mandate, my utility collects money from all customers that covers the gap between what they pay to solar owners and the value of that energy. For melons, imagine a small markup whose resulting revenue gets distributed to local farmers to grow melons in Boston, where it costs more per melon than in warmer climates.

Renewable Energy Charge = Organic Certification

Similar to the distributed solar charge, this covers the cost of transitioning away from fossil fuels by procuring renewable electricity. You might be thinking, “I thought solar and wind are the cheapest sources of electricity - why do they need a subsidy?” The reason is mainly because they are competing against sources of generation that are already built and have recouped much of their investment and partly because New England is a bad place (compared to other parts of the US) to build renewables. This charge is a little deceiving because the majority of the cost of procuring clean energy is baked into the generation charge- more on that in subsequent posts. Just like organic melons, here we are paying slightly more for a product that is better for the climate.

Energy Efficiency = Melons for All Contribution

Before you run to donate, no, this is not a real charity. But imagine one whose mission is to help people do more with fewer melons. It’s similar for efficiency; this charge translates into subsidies for energy efficient appliances and custom projects like weatherizing buildings and upgrading old equipment. In theory everyone benefits, but research shows that it is predominantly wealthier households taking advantage of these subsidies.

Phew- we’re done! I know that was a lot. Deep breaths. If you are feeling lost, I promise that you will never be quizzed on this material. More importantly, you should feel lost; this stuff is like learning a foreign language. In the next post, we’ll look at what drives the prices for the most significant charges. But for now, go have yourself a melon and call it a day.